History

This article was originally published in the March 1952 issue of Outdoor Life magazine. Used with permission.

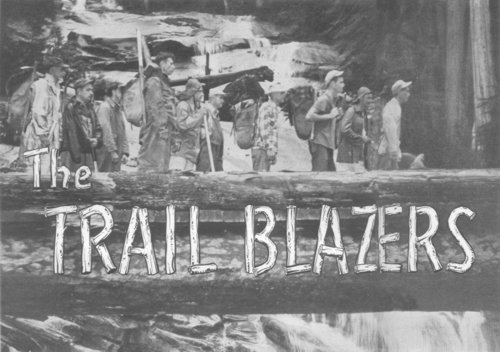

The going is momentarily easy as club members cross an old trestle in their hike toward mountain lakes far beyond any trail.

by HOWARD E. JACKSON

When the alarm routed me out of bed at 2 a.m. that September morning I was raring to go. Even though I was a little soft, I figured this tnp with a bunch of guys who call themselves the Trail Blazers would be no tougher than some I'd taken before,. including shooting rivers in foldboats or exploring caves In the Pacific Northwest.

The two-day Itinerary called for a 2:30 a.m. rendezvous In Seattle, Wash.; a stop at a hatchery to pick up some fish fry; and a hike into the high reaches of the Snoqualmie National Forest in the Cascade Mountains. Then we'd plant trout In half a dozen of the jewellike lakes and potholes which nestle up there among evergreen-covered ridges. And finally we'd fish those same remote high-country waters.

The Trail Blazers are good-natured Joes, from all walks of life who love the back country, are willing to see that Its lakes and streams and potholes are kept well stocked, and delight in fishing those high lakes beyond the end of the trail. These are the sole aims of their club.

Promptly at 2:15 Frank Mortimer drove up with Verne Whitham. I stowed my loaded packboard In the rear of the car, slid in next to Verne, and Frank took off down the deserted streets. Fifteen minutes later we met the rest of the fellows at a fork in the road. We numbered an even dozen. Three of us were gueats: Jack Rollo, Lyle Tillotson, and I- The rest (Frank and Verne included) were club members: Don Butler, Bob Johnson, George Kniert, Clayton Kilbourne, Jack Mathewson, John Pfister, and Charley Yadon.

Charley was in charge. He led our four-car caravan down the highway to keep a 3 a.m. date with C. J. Nixon, superintendent of the Tokul Creek Hatchery near Fall City. With minutes to spare, we stopped beside the long low buildings in which Nixon and his crew raise some 10,000,000 fish fry annually.

"How many will It be this time?" Nixon asked cordially. "We figure 2600," Charley told him. "All rainbows. "

The superintendent hung a pail on the scales, added water, then put in thirteen ounces of one-inch, two-month-old rainbow trout. The tiny fish bad been "starved" for a day. to condition them for the trip. Club members had learned that if this isn't done. the fry consume too much oxygen, give out too much waste, and die.

"How do you know you have 2.600?" I asked Nixon after he'd weighed out the fry.

"By count and recount we know there are 200 fry to the ounce," he answered, pouring the fry into the six-gallon. burlap-wrapped pack can.

The can had been previously cleaned and three-quarters filled with cold water plus ice. It could hold up to a pound of fry, Charley explained, as he covered its small opening with a burlap pad held taut by a heavy rubber band. The carrying: can was one perfected and made by the club. The hatchery supplied the try free.

Author Howard Jackson (L) and Governer Arthur Langlie (M) present Trail Blazer President Gordie Herbert (R) with the Outdoor Life Conservation Award in 1952. Photo from Clayton Kilbourn collection.

"So you're off for the Nordrum basin. What lakes do you aim to stock?" Nixon asked.

"We thought we'd put about half the fry in Nordrum and divide the rest among Judy, Rock, Lunker, High Low, and two small potholes," Charley replied, as though the job would be as simple as pouring milk into a glass.

The look on Nixon's face made me uneasy. I knew the men stock lakes and streams in country from 2.000 to 10,000 feet high—terrain so rugged that no trails reach 90 percent of its lakes and potholes. That's how the fellows in this club got their name—the Trail Blazers.

"You have a job on your hands," Nixon said solemnly as he walked us to the door.

At the cafe where we stopped for breakfast, a few of the more daring members suggested taking a shortcut to Lake Nordrum, but Charley was all for sticking to the Taylor River trail. He conceded that it would mean hiking two miles more than usual, because of a washed-out bridge, but pointed out that none of the group had ever traveled over the proposed shortcut, and that aerial and contour maps indicated 6,OOO-foot ridges studded with canyons and rock cliffs.

What was I in for, anyway? I started to do a little worrying, but after we picked up our fire permit and turned off toward the mountains. the narrow logging road swept beneath our headlights at such an alarming rate I couldn't even do that. The cars scooted over flimsy trestles and skidded around sharp turns as though they were on a well-lit track.

Suddenly the road ended at the washed-out bridge. Rain began to fall. As we piled out of the cars and bumped our heads against the low-slung clouds. it was obvious that shortcuts were out of the question. We had no choice but to keep to the trail.

We all had packboards carrying food, sleeping bags. first-aid kits, and fishing gear the average load being about fifty pounds. Most of us carried our fishing rods in aluminum containers Clayton Kilbourne had the dubious honor of carrying the pack can of fish fry.

Hiking along the last stretch of the old logging road wasn't bad, despite the drizzle. However, when the read ended and a single-file trail began, we ran smack into a blowdown log jam that towered twenty feet high in places. My pack felt like a piano on my back as I tried to pick my way up and over those giant jackstraws. When I tried to crawl beneath them the pack would get wedged, bringing me up short. I was annoyed until I saw Clayton. Every time he rope-walked along a log. the sloshing water in the pack can threw him off balance, and when be ducked under the logs he got a quick, cold shower as water cascaded through the thick burlap cover and down his neck.

Editor's note: The seventh Outdoor Life Conservation award goes to the Trail Blazers, sportsmen’s club of Seattle, Washington. For further details about the award see page 75.

It look just 200 feet of this going to tire me. And when we got out of the blowdown, the trail ahead didn't look promising. It was narrow, brush-lined. and flanked by sky-scraping trees that grew so thick they hid the leaden sky from view. Everything was wet. Drizzle-soaked leaves dripped on us. and whenever we bad to leave the trail the sodden bushes sprayed us from bead to foot. Rivulets of persperation ran down our backs and legs as we plodded up the never-ending switchbacks through the dank but weirdly beautiful forest.

I had to stop frequently, gasp for air. and let my pulse calm down. The distance from the windfall to the top of the ridge was only 3 1/2 miles, but it was also a climb of 3,400 feet. I was thankful when we reached the halfway stream where the water In the can of fry was to be replaced.

I began to realize: now why these fellows had raced like crazy along the highway and logging roads, scrambled like mad ants over the windfalls, and stomped up the twisting trail without a pause. They didn't want those fish fry to die By sticking to schedule and moving constantly to aerate the water in the can, they kept the fry alive.

Although the Trail Blazers have made more than 300 stocking trips and planted over 2,000,000 trout fry in barren or depleted high lakes. relatively few trips have been unsuccessful. One lot of fry was lost because of metallic poisoning from unpainted cans, but the men never let that happen again. Another time 10,000 fry failed to survive a trip because the water temperature in the cans rose a dozen degrees above the vital range—48 to 50 degrees. Since then the parties do not rely upon reaching cold streams or snow. but pack along a hunk of ice which they chip into the cans as it's needed.

On this trip the water temperature rose only a degree or two. so icing was not necessary. Before refilling the can. Clayton checked the stream-water temperature, which was correct within a degree, so it could be used without further ado.

I was stiff when I stood up after our rest and thus grateful to Verne for helping me shoulder my packboard. The second half of the climb up the tortuous trail was a repetition of the first. with a little excitement added when Jack Rollo stepped on an underground nest of yellowjackets. We scrammed—but quick. The buzzers proved to be a

OUTDOOR LIFE March, 1952 38,39