Biographies

George Lewis, 1920-1989

by Virg Harder, 2001

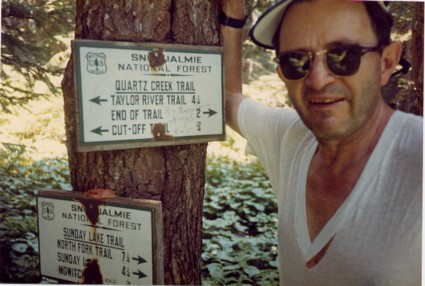

Active… dedicated… friendly… helpful… those are only four of many attributes that come to mind as I think of George Lewis. George traipsed around Washington’s Cascade mountains for many years. But, he also did much more.

During some the 1930’s depression years, he became well acquainted with a portion of the Cascades as a member of the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps). He was stationed at Camp Brown, helped build a number of trails, and frequently was sent by the camp cook (when he discovered George liked to fish) to catch trout for meals. George became an excellent trout provider. George also became acquainted with the Newhalem area of the North Cascades while employed by Seattle City Light.

He was a member of the armed forces during WWII. During basic training, his company went on a 25-mile hike with "full field" (60 lb) packs. At the end of the hike, his company was relaxing on a parade grounds. Soldiers were complaining mightily about how tired they were. George, an excellent gymnast, decided to show them that he still had energy. He started doing back flips. He hadn’t been doing them very long when an ambulance came roaring up, two medics hopped out, grabbed him, stuck him inside the ambulance, and headed for the hospital. Some officer had reported that any soldier who did back flips after a 25-mile hike had to be crazy. His war stories made me glad I was in Europe while he was on Guadacanal.

After George returned from his hitch. He opened a watch repair/jewelry store, and did something unique for Seattle girls. Several organizations sponsored gymnastics for boys, but nobody sponsored gymnastics for girls. George put together a gymnastics organization for girls. It was a success. A couple of his girls participated in more than one Olympics, and George was an instructor in one of the Olympics. If memory serves me correctly, one of his students won a silver medal.

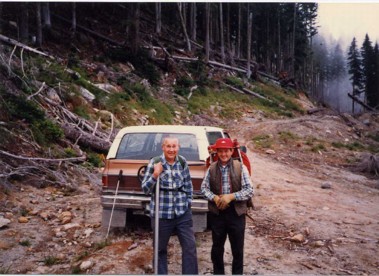

Con Mattson (left) and George Lewis (right), getting ready to head for a lake.

After about 15 years as a small business owner, George decided to become a horology teacher at North Seattle Community College. He very much enjoyed working with young people—helping them learn. Helping young people learn was his vocation, helping people enjoy Washington’s mountain fishing was his avocation.

George became a Trail Blazer in 1954. Since the "Rules of the Game" were quite different then from what they are now, George didn’t sponsor any lakes until 1956. From then on, his sponsored trips cover a litany of lakes.

When one thinks of lakes that George stocked, one is almost overwhelmed. Goat, Horseshoe, LeFay, Merlin, Nimue… Lennox, Bear… Nine Hour, Rainy… Big Cougar, Little Cougar, Anderson Gap… Upper and Lower Garfield… My Lake, Snoqualmie Lake Pots, Tinkham Peak Pots. All those listed, as well as a number of others not identified for obvious reasons, are lakes that George "maintained" over the years. He handled them using "seat-of-the-pants" principles, but the lakes "weathered" well.

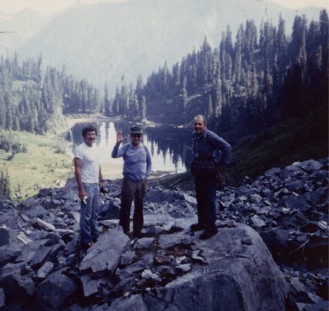

From Left to Right: Dick Foxall (one of George’s former gymnast students), George Lewis, (at one of his favorite lakes), Gene Rose.

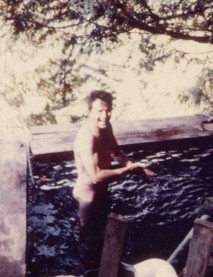

Scenic Hot Springs 9/25/83 (about 6’ square, 1 pool, no deck). George Lewis knew how to enjoy the mountains.

The number of trout fry that George planted is impressive. One must realize that until the mid-1950’s, quite a few plants ranged from five to fifteen thousand; thus, one could build up incredible totals rather quickly. Excluding Goat and Horseshoe, the lakes George planted were relatively small. Consequently, George’s number of trout per plant usually was 200 or less. Still he stocked over 100,000 trout fry.

When one grasps the implications of the number of lakes George planted, and the number of trout he planted, one realizes that George was giving — giving much more than he took. He gave hundreds of people the opportunity to enjoy their backcountry experiences more — by providing tens of thousands of opportunities to catch fish.

George hid no lakes. He withheld no information. Anyone who asked George a question received an honest answer, no stonewalling or evasive mumbling. He did have his failing, however. He did not know what the word "tired" means. He had only one gear: Go. He also followed the principle of "never go around when you can go over." And, finally, he almost always succumbed to traveling the most brushy route; he was particularly partial to head-high huckleberry bushes. One could almost hear him purr on the upper third of the route to Nine Hour Lake.

All the data in the preceding paragraph merely shows that George was mortal, not omniscient. His fallibility, however, can easily be forgiven and forgotten when one thinks of all the good things George did. He was a credit to his family. He was a credit to the gymnastic community. He was a credit to his profession. He was an outstanding teacher, as well as a credit to education. And, he was a credit to the Trail Blazers.